At the end of the last post, I detailed the story beats thus:

Act 1 – opening before investigation, setup, initial enquiries, decision to progress

Act 2A – maybe side story (love interest?), detailed investigation, first obstacle,

Act 2B – the investigation gets more difficult, MC suffers biggest obstacle, things look bad, oh – hang on…

Act 3 – new impetus, new ideas, closing in on the culprit, knocking red herrings aside, final disclosure, rounding up, return to normality

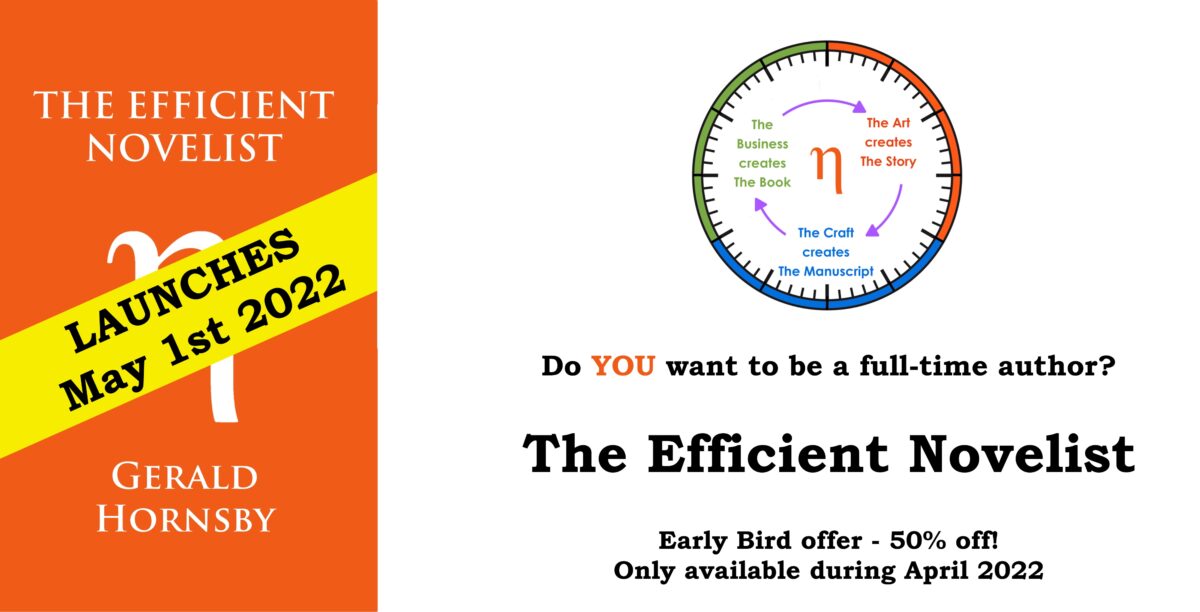

At this point, I’m eyeing up one of my favourite processes, which is 100% the key to all of my novel writing in the past five years – maybe longer.

Continue reading →